We are grateful to Tom Palmer (Atlas Foundation) for his tribute to this great monument of human history which is celebrated in English speaking countries but which inspired the 1789 French “Declaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyens”. By the way we advised you to watch Daniel Hannan’s excellent video on ICREI October 18th 2013

We are grateful to Tom Palmer (Atlas Foundation) for his tribute to this great monument of human history which is celebrated in English speaking countries but which inspired the 1789 French “Declaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyens”. By the way we advised you to watch Daniel Hannan’s excellent video on ICREI October 18th 2013

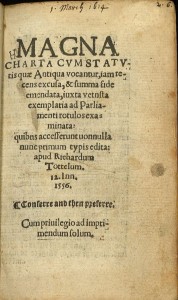

Magna Carta is celebrating its 800th birthday. This great event is significant not only for the English, or even the English-speaking nations, but for all of humanity. On this occasion, it is worth remembering some important facts about the “Great Charter of Liberties.”

I. Constitutional liberty and the rule of law are not uniquely English

A British member of the European Parliament, Daniel Hannan, recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal that, “It was at Runnymede, on June 15, 1215, that the idea of the law standing above the government first took contractual form.”

Hannan stressed Anglo-Saxon origins of the principles of liberty and boldly concluded, “I recount these facts to make an important, if unfashionable, point. The rights we now take for granted—freedom of speech, religion, assembly and so on—are not the natural condition of an advanced society. They were developed overwhelmingly in the language in which you are reading these words. When we call them universal rights, we are being polite.” I admire Dan greatly, but I think his history is in error. For one thing, I learned some time ago to be very careful with such terms as “first,” “last,” “never,” “always,” and “only,” and I encourage him to be careful, as well.

Magna Carta, the “Great Charter of Liberties,” was most certainly not the first contractual limitation on government powers. By no means. King John was not the only warlord whose powers were clipped by such means. Magna Carta was part of a much wider European movement of charters, communes, consent-based oath fellowships, and more, which carved out spheres of freedom and provided instruments to contain power and violence. By the 13th century, guilds and urban communes were being organized all over Europe and they secured peace and liberty for greater and greater numbers of people. Trade was increasing across the continent and, as the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne noted, that led to greater demands for liberty, for “trade made of the merchant a man whose normal condition was liberty.” Of the needs of the new civil society, ‘‘the most indispensable was personal liberty. Without liberty, that is to say, without the power to come and go, to do business, to sell goods, a power not enjoyed by serfdom, trade was impossible.” A common European maxim was “City air makes one free” (“Stadtluft macht frei”), not only after Magna Carta but for centuries beforehand in the cities of Europe.

Voluntarily organized associations, such as guilds and communes, secured individual freedom for their members. As the British historian Antony Black put it, “The crucial point about both guilds and communes was that here individuation and association went hand in hand. One achieved liberty by belonging to this kind of group. Citizens, merchants, and artisans pursued their own individual goals by banding together under oath.”

Civil society emerged from such associations. The right to associate was sometimes forcefully asserted against the powers of rulers and sometimes secured under royal charter, often at the expense of local feudal powers. King John himself had been involved in such acts, as in the charter of Ipswich of 1200, which involved a charter from the king granting the citizens exemption from a variety of burdens, including the billeting of troops (a right specifically protected in the Third Amendment to the U.S. Constitution), and guaranteeing protection of property and promising that “justice shall be done them according to the ancient custom of the borough of Ipswich and of our free boroughs.” It was secured through an oath of all the citizens, taken on Sunday, July 2, 1200, when they swore to obey and assist their own elected officers in protecting the liberties and customs of the borough.

Magna Carta cannot be understood aside from the European-wide movement of communes. Indeed, Chapter 61 of Magna Carta of 1215 specified empowering 25 barons to “observe, maintain and cause to be observed the peace and liberties which we [King John] have granted and confirmed to them by this our present charter,” and to do so “with the commune of all the land.”

One could mention many precedents for Magna Carta, including Henry I’s “Charter of Liberties,” issued in 1100, which made various concessions to the barons and knights; the Assizes of Ariano, promulgated in 1140 by King Roger II of Sicily; and, shortly after Magna Carta, the Golden Bull of Hungary of 1222, signed by King András, which instituted a long period of constitutionalism in central Europe; the Constitutions of Melfi issued by Emperor Frederick II in 1231; and numerous others. Even the important terms regarding “the law of the land” and “trial by one’s peers,” which later reappeared in the U.S. Constitution, predated Magna Carta; they can be found, for example, in a constitution agreed to by Emperor Conrad II in 1037, which declared that no vassal should be deprived of an imperial or ecclesiastical fief “except in accordance with the law of our predecessors and the judgment of his peers.”

Thus, Magna Carta is situated within a comprehensive European struggle over powers, immunities, rights, and liberties. Magna Carta was by no means the first occasion in which, in Hannan’s phrasing, “the idea that governments were subject to the law took written, contractual form.” The movement for liberties and immunities was sweeping the continent, as well as England. Magna Carta was vitally important, not because it was unique, but primarily because it was remembered — a point to which I will return.

II. Magna Carta was embedded in the struggle for freedom of the church

Magna Carta was also part of a wider European movement for the freedom of the church. That was not the “separation of church and state” as we understand the idea, but it was definitely the source of what we now understand by that phrase. It originated in the attempt of each to gain mastery over the other and their general failure to do so. In one of the more dramatic moments of that struggle, Pope Gregory VII in 1075 laid down the gauntlet in the Dictatus Papae and concluded that the pope “may absolve subjects from their fealty to wicked men.” It was a bold claim in a great struggle between the church and the secular powers.

King John himself struggled with the papacy over control of the English church. He was excommunicated and the kingdom was laid under interdict in 1208, an interdiction that made things quite difficult for the whole Christian population of England, as no communion was offered and none were given Christian burial. John returned to the church in 1213, evidently to shore up his powers against the emerging coalition of barons. On May 15, 1213, in Dover, King John granted to “God, the apostles Peter and Paul, the Holy Roman Church our mother, and to our lord pope Innocent III and his catholic successors the kingdoms of England and Ireland, with all our right and appurtenances for the omission of our sins and all our race, living and dead.” He then received it back as a fief, a feudal grant, in exchange for pledging his loyalty and his homage, the latter of which entailed substantial payments to the papacy, but “saving to us and our heirs our ordinances, our freedoms, and our royal status.” Thus, his kingdom was held of the church and secured, he evidently hoped, a status both feudal and sacred.

The leaders of the church, as rivals to the secular powers, maneuvered for the church’s advantage, which certainly helps to explain why Magna Carta ends and concludes with affirmations of the freedom of the church. It was agreed “that the English church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished and its liberties unimpaired,” and would enjoy “freedom of elections, which is thought to be of the greatest necessity and importance to the English church.” The guarantees to the church in the first chapter were followed by the vitally important promise that “We have also granted to all the free men of our realm for ourselves and our heirs for ever, all the liberties written below, to have and hold, them and their heirs from us and our heirs.” That promise, following the freedom of religion, has echoed down the ages.

Had the conflict between the Roman church and the secular powers not been under way, Magna Carta would have been unthinkable. Magna Carta was a part of a broad European movement for the freedom and independence of the church, not a unique expression of the Anglo-Saxon (or Anglo-Norman, or Anglo-Angevin) character.

III. Magna Carta was not a choice of strategy in an ideological movement to achieve equal liberty for everyone, but it did set the stage for equal liberty

The movement that led to Magna Carta and the document agreed to by the king and barons — and, shortly thereafter, annulled by the pope and disregarded by King John — was not a part of an ideological movement to extend individual liberty and the rule of law to everyone. It was, as we have been reminded by cynics many times, a struggle over power and wealth. Nonetheless, that struggle gave rise to arguments about justice, about law, and about rights and liberty that played key roles and had a great influence on the ideas of, the movement for, and the implementation of constitutionally limited government with a mandate to protect liberty and legal and political restraints on those who exercise that mandate.

In his struggle for his possessions and his empire on the European continent, King John deployed a great array of stratagems to extract money, manpower, and other resources from the English barons and, through them, from the people. Those stratagems included acts of extortion, maximal extraction of feudal dues, the sale of privileges and immunities against powers that had been amassed by his father Henry II, and deployment of the legal system — the sale of justice — as a revenue device.

The loss of Normandy in 1204 was a terrible blow to a ruler descended from William the Conqueror. The taxes and military services that King John demanded as means to recover his lost domain caused resentment and discontent. Civil war became the greater danger after he rolled the dice and he and his allies suffered the epic defeat of the Battle of Bouvines in 1214 at the hands of the French monarch Philip II Augustus.

The political struggles of the time are not so easily understood today. They were not constitutional struggles of the sort with which we so often concern ourselves today, in which branches or levels of government argue over their powers or citizens assert their rights against the powers of the state. The state as such could barely be said to have existed at all. The distinction between the state and the personal possessions of the king was blurry. It was, moreover, a family affair. Power in England and France was contested, for example, among King Henry II, his wife, and his sons, including John — each with their various allies. Family squabbling took place on the battlefield. In effect, there was no state as we understand it today, as something that is in some way independent of the personal prerogatives of the holders of power. Those power relationships were increasingly constrained by an evolving system of law, of rules that might be applied to both rulers and ruled, and by an emerging constitution that was distinct from the personal powers and possessions of the powerful.

One of the consequences of the wider movement of which Magna Carta was a part was to distinguish the administration of the king’s interests from the administration of the law. Liberty under the rule of law was an unintended consequence of the struggle for power among many contenders in a widely decentralized European political system.

IV. Magna Carta as political philosophy

Magna Carta played an important role in the development of the political theory of limited government. Specifically, it and many similar charters helped to subordinate power to law.

The debates of the time involved a complex array of arguments for and against the claims of kings, emperors, popes, urban communes, shires, guilds, citizens, and simple individuals. On behalf of their supreme power and exalted status, Europe’s Christian kings claimed the authority of the Bible, notably Romans 13 (“Let every soul be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and the authorities that exist are appointed by God. Therefore whoever resists the authority resists the ordinance of God, and those who resist will bring judgment on themselves”) and 1 Corinthians 15 (“But by the grace of God I am what I am: and his grace which was bestowed upon me was not in vain …”). Advocates of royal power argued that the king ruled by divine concession and concluded that, in historian Walter Ullman’s phrase, “The individuals as subjects had no rights in the public field. Whatever they had, they had as a matter of royal grace, of royal concession.”

The Church, for its part, also invoked biblical passages, notably Matthew 22 (“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”). Church leaders also used very adroitly the rediscovered Digest of Justinian, the compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire; some of the most powerful of popes were lawyers. Feudal lawyers cited custom and oath as sources of — and limits to — authority. Prof. Richard Helmholz of the University of Chicago Law School has argued quite persuasively that the text of Magna Carta, for example, was strongly influenced, both in substance and in choice of language, by the Roman and canonistic (church) traditions of law, the ius commune, that was being developed and taught on both sides of the English channel.

The individual as a bearer of rights, and social relations as the product of the free exercise of those rights, both emerged from arguments and practices drawn from Roman law, Christian theology, and Germanic oath-based associations (which was at the root of both feudalism and the new cities of Europe). The struggle for power and rights generated what the historian Sir Henry Sumner Maine called in his book Ancient Law, “a movement from status to contract,” that is, from a society where birth determined all of your relationships to one in which choice and consent formed those relationships.

V. The importance of Magna Carta today

What relevance do the words of Magna Carta have today? Only a few still find their place in written law, most notably those of Chapter 39 that, after paraphrase and reinterpretation, found their way into the U.S. Constitution as the right to due process of law and trial by jury.

Magna Carta’s greatest importance may be that it created for those whom Hannan calls the “English-speaking peoples” a narrative that has exceptional power. Magna Carta was cited in the English Petition of Right of 1628 against Stuart tyranny. The British colonial assemblies in America declared Magna Carta to be part of the law of the province. In 1638, the colonial assembly of Maryland declared “that the inhabitants shall have all their rights and liberties according to the great charter of England,” an act that was vetoed by the king’s representative as inconsistent with “the royal prerogative.” The American colonists who struggled for their rights asserted the provisions of Magna Carta forcefully. Those provisions figured prominently in appeals of the colonial legislatures against the British crown and parliament.

The American founders also did precisely what Hannan denies. Hannan claims of the American colonists that “Nowhere, at this stage [having just cited a text of 1774], do we find the slightest hint that the patriots were fighting for universal rights.” In fact, they drew strongly on the idea of universal rights, known as natural rights. The natural rights tradition had been articulated brilliantly in English by the libertarians of the 17th century, known as the Levellers, and by the great physician, philosopher, and political activist John Locke.

Let us, to be sure, cite Magna Carta and the U.S. Constitution as the bedrock of our own tradition of liberties. But let us not thereby consign the inheritors of other traditions and other identities to slavery and tyranny.

The moving power of the American formulation of liberty lay precisely in the merger of abstractly formulated and thus universal rights with concretely situated historical rights.

The historical memory of Magna Carta, when combined with a bold appeal to claims of universal rights — the “truths” that are “held to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” — allow Americans to draw on powerful sources of legitimacy for limits to power and the free exercise of rights. Americans can be both traditional and radically universalistic at the same time, asserting both historically situated rights that appeal to a common yearning for identity and universal truths that provide moral strength in the face of power. In this, Americans are heirs to the Levellers, who also called on the ancient constitution. Here I have in mind primarily John Lilburn, who insisted on the ancient authority and power of juries to stop injustice. I also have in mind William Walwyn (who referred to Magna Carta as “that mess of pottage”), who defended the rights to religious freedom of Catholics, and Richard Overton, who argued:

“To every Individuall in nature, is given an individuall property by nature, not to be invaded or usurped by any: for every one as he is himselfe, so he hath a selfe propriety, else could he not be himselfe, and on this no second may presume to deprive any of, without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature, and of the Rules of equity and justice between man and man … For by naturall birth, all men are equally and alike borne to like propriety, liberty and freedome, and as we are delivered of God by the hand of nature into this world, every one with a naturall, innate freedome and propriety (as it were writ in the table of every mans heart, never to be obliterated) even so are we to live, every one equally and alike to enjoy his Birth-right and priviledge; even all whereof God by nature hath made him free.”

The merger of the two appeals — to historically situated rights that provide a sense of identity and to abstract and universal justice that appeal to reason and conscience — provides a powerful formula for liberty.

Today’s challenge worldwide for advocates of liberty and the rule of law is to identify in myriad cases the local roots in each culture of constitutional restraint on power and respect for the right to freedom, and to connect those historical roots to the contemporary universal libertarianism that is spreading worldwide. Those roots are definitely there to be excavated, not only in the history of the English-speaking peoples, but everywhere we care to look:

in Russia, where libertarians remember the city of Novgorod, known for the freedom and independence of its citizens, which enjoyed its charter and a legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, under Yaroslav the Wise, and whose boyars in 1136, 79 years before Magna Carta, dismissed their prince, Vsevolod Mstislavich, and instituted the practice of an elective executive with limited powers;

in Islamic civilization, for which the prophet laid down standards of respect of the rights of individuals and adherence to justice among those with power, a civilization from which a thousand years ago emerged powerful ideas of law and reason that had a significant influence on the ideas of liberty in Christian Europe;

in the legal and political traditions of West Africa, in which kings were not autocrats or dictators, but were traditionally limited in power and expected to serve as judges and peacemakers, with powers granted by the community and not exercised against it;

in China, where great thinkers such as Lao Tzu, Confucius, Mencius, and Su Tung-p’o enjoined restraint, modesty, and justice among rulers and respect for the rights of the people.

One could go on. Liberty under the rule of law is not merely an English birthright; it is a human birthright.

Magna Carta teaches and inspires. What it should teach us, however, is not the special privilege of the English-speaking peoples, but a universal message of law over violence and of freedom over power. My colleagues around the world, in many other civilizations, have their own Magna Cartas, as well, and, like Sir Edward Coke in 17th century England, they are bringing them forth as tools to limit power and inspire people to demand their rights.